Mercedes 300d coupe

If anyone wants to know why the Mercedes W124 and W201 were considered so influential in their day, consider their predecessor, the W123. Conservative even by German standards, these iconic cars need no introduction and, with 2.7 million made over ten years, are still plentiful. I was quite happy to find this blue, top-of-the line example from the final year of the production run and have to applaud Virginia for continuing to make such elegant license plates with characters actually stamped into the metal. They’re certainly a more fitting complement to this sedan’s classic lines than the non-standard turn signal lenses seen here.

If anyone wants to know why the Mercedes W124 and W201 were considered so influential in their day, consider their predecessor, the W123. Conservative even by German standards, these iconic cars need no introduction and, with 2.7 million made over ten years, are still plentiful. I was quite happy to find this blue, top-of-the line example from the final year of the production run and have to applaud Virginia for continuing to make such elegant license plates with characters actually stamped into the metal. They’re certainly a more fitting complement to this sedan’s classic lines than the non-standard turn signal lenses seen here.

Where the models which followed the W123 followed the aerodynamic rule book, even raising the bar, these cars were rather staid even when new, representing the final chapter in Mercedes’ book on the post-war sedan. Note the very small tail fins, a vestige of the once significant American influence on the West German automobile.

Despite being the first Benz styled under Bruno Sacco, the need to fit the car into the existing lineup meant it continued in the footsteps of the W108/9 and W114/5, and was especially influenced by the low and wide W116 S-class. The lack of a wedge shape lends these cars a deceptively compact appearance, but they were larger than earlier models, with a 110 inch wheelbase (about 107 inches for the coupe).

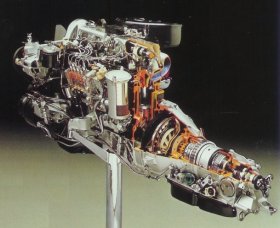

While the W123 is sought after for its rustic charm, Mercedes didn’t set out to make an anticar. They were simply getting the most mileage out of existing styling and engineering themes in a car which fulfilled an uncommonly diverse array of roles, from underpinning an upmarket coupe to serving as an ambulance, as well as a taxicab and an executive sedan. In this case, the engineering was largely a refinement of concepts first introduced in the “stroke-8” models of 1968, also known as the W114 (six cylinder) and W115 (four-cylinder and diesel, sans front subframe). With semi-trailing arms in the rear and a hefty safety cage with crumple zones, it remained thoroughly up-to-date under the skin. The biggest departure from predecessors was the deletion of a front subframe from the most expensive models, which joined their more plebeian brethren in directly mounting major mechanicals to the main structural components.

Legendary Mercedes engineering notwithstanding, straight line motivation in US-market models was a problem. The 240Ds and non-turbo 300Ds were obviously slow. The initial alternative was the 280E, which in US form, was rather disappointing, with 140 horsepower pushing 3300 pounds. A bigger issue, though, was the transmission’s second-gear start and a 1-2 upshift which occurred at around 4500rpm, well before the power peak. As the company always tuned its engines to deliver the most power in the upper midrange, highway performance was good for the era, but for American conditions, especially during the double-nickel era, better low-end response was needed.

Legendary Mercedes engineering notwithstanding, straight line motivation in US-market models was a problem. The 240Ds and non-turbo 300Ds were obviously slow. The initial alternative was the 280E, which in US form, was rather disappointing, with 140 horsepower pushing 3300 pounds. A bigger issue, though, was the transmission’s second-gear start and a 1-2 upshift which occurred at around 4500rpm, well before the power peak. As the company always tuned its engines to deliver the most power in the upper midrange, highway performance was good for the era, but for American conditions, especially during the double-nickel era, better low-end response was needed.

All of this helps to explain why Mercedes found it wise to replace the 280E with the 300D turbodiesel in 1982. With its beefier low-end and first-gear start, it was punchier in American suburban traffic. Given the 280E’s prodigious drinking habit, and the fact that GM was heavily advertising diesels at the same time that VW was able to sell Rabbits with substantial mark-ups, this approach made sense. Our featured car, a 1985 model, received a much taller rear axle ratio to boost economy along with a higher torque converter stall speed to help the turbocharger boost more rapidly.

Our featured car, a 1985 model, received a much taller rear axle ratio to boost economy along with a higher torque converter stall speed to help the turbocharger boost more rapidly.

The 300D turbodiesel was never, however, an especially miserly car and despite such efforts to improve its efficiency, I suspect many buyers would’ve been better off in a Volvo with a 2.1 liter turbocharged gas engine, which would have more cheaply and effectively validated both their social conscience and (secret) need for performance. If that strikes readers as too agricultural a car to compare to the Benz, it’s important to note the Peugeot 505 was still available in those days and didn’t suffer from the brittle quality its front-drive successors were known for. I don’t even need to mention the BMW E12 and E28.

Now time for a confession: modern day fans of the W123 qualify in my mind as some of the most sentimental enthusiasts, with an embrace of cloying stereotypes which ranks right up there with lovers of the Saab 900 and Volvo 240. Claims of 40 mpg and iron-clad reliability are common, so allow me this opportunity to dispel such myths. As much as I love these cars, it’s important to understand what they are and what they are not.

They are not the most reliable cars in the world. Any decent car will last 500, 000 miles if a loving owner replaces major components as they break. I would wager that a large number might even do so with less fuss and expense than a W123, if one focuses purely on mechanicals (and not body hardware, where the Mercedes has a genuine advantage). The reputation for dependability these cars enjoy stems from the fact that they were sold alongside luxury cars from Detroit during an era when six-digit odometers were a rarity. The accidental charm they possess prompts their continued repair and resale while their hugely influential successors, on the other hand, do not benefit from the same affinity.